How do you tell what a superhuman AI's values are? ( picture: ittybittiesforyou - see bottom)

Robin Hanson says that it is more important to have laws than shared values. I agree with him when ‘shared values’ means that shared indexical values remain about different people, e.g. If you and I share a high value of orgasms, you value you having orgasms and I value me having orgasms. Unless we are dating it’s all the same to me if you prefer croquet to orgasms. I think the singularitarians aren’t talking about this though. They want to share values in such a way that AI wants them to have orgasms. In principle this would be far better than having different values and trading. Compare gains from trading with the world economy to gains from the world economy’s most heartfelt wish being to please you. However I think that laws will get far more attention than values overall in arranging for an agreeable robot transition, and rightly so. Let me explain, then show you how this is similar to some more familiar situations.

Greater intelligences are unpredictable

If you know exactly what a creature will do in any given situation before it does it, you are at least as smart as it (if we don’t include it’s physical power as intelligence). Greater intelligences are inherently unpredictable. If you know the intelligence is trying to do, then you know what kind of outcome to expect, but guessing how it will get there is harder. This should be less so for lesser intelligences, and more so for more different intelligences. I will have less trouble guessing what a ten year old will do in chess against me than a grand master, though I can guess the outcome in both cases. If I play someone with a significantly different way of thinking about the game they may also be hard to guess.

Unpredictability is dangerous

This unpredictability is a big part of the fear of a superhuman AI. If you don’t know what path an intelligence will take to the goal you set it, you don’t know whether it will affect other things that you care about. This problem is most vividly illustrated by the much discussed case where the AI in question is suddenly very many orders of magnitude smarter than a human. Imagine we initially gave it only a subset of our values, such as our yearning to figure out whether P = NP, and we assume that it won’t influence anything outside its box. It might determine that the easiest way to do this is to contact outside help, build powerful weapons, take more resources by force, and put them toward more computing power. Because we weren’t expecting it to consider this option, we haven’t told it about our other values that are relevant to this strategy, such as the popular penchant for being alive.

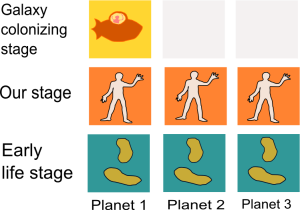

I don’t find this type of scenario likely, but others do, and the problem could arise at a lesser scale with weaker AI. It’s a bit like the problem that every genie owner in fiction has faced. There are two solutions. One is to inform the AI about all of human values, so it doesn’t matter how wide it’s influence is. The other is to restrict its actions. SIAI interest seems to be in giving the AI human values (whatever that means), then inevitably surrendering control to it. If the AI will inevitably likely be so much smarter than humans that it will control everything fovever almost immediately, I agree that values are probably the thing to focus on. But consider the case where AI improves fast but by increments, and no single agent becomes more powerful than all of human society for a long time.

Unpredictability also makes it hard to use values to protect from unpredictability

When trying to avoid the dangers of unpredictability, the same unpredictability causes another problem for using values as a means of control. If you don’t know what an entity will do with given values, it is hard to assess whether it actually has those values. It is much easier to assess whether it is following simpler rules. This seems likely to be the basis for human love of deontological ethics and laws. Utilitarians may get better results in principle, but from the perspective of anyone else it’s not obvious whether they are pushing you in front of a train for the greater good or specifically for the personal bad. You would have to do all the calculations yourself and trust their information. You also can’t rely on them to behave in any particular way so that you can plan around them, unless you make deals with them, which is basically paying them to follow rules, so is more evidence for my point.

‘We’ cannot make the AI’s values safe.

I expect the first of these things to be a particular problem with greater than human intelligences. It might be better in principle if an AI follows your values, but you have little way to tell whether it is. Nearly everyone must trust the judgement, goodness and competency of whoever created a given AI, be it a person or another AI. I suspect this gets overlooked somewhat because safety is thought of in terms of what to do when *we* are building the AI. This is the same problem people often have thinking about government. They underestimate the usefulness of transparency there because they think of the government as ‘we’. ‘We should redistribute wealth’ may seem unproblematic, whereas ‘I should allow an organization I barely know anything about to take my money on the vague understanding that they will do something good with it’ does not. For people to trust AIs the AIs should have simple enough promised behavior that people using them can verify that they are likely doing what they are meant to.

This problem gets worse the less predictable the agents are to you. Humans seem to naturally find rules more important for more powerful people and consequences more important for less powerful people. Our world also contains some greater than human intelligences already: organizations. They have similar problems to powerful AI. We ask them to do something like ‘cheaply make red paint’ and often eventually realize their clever ways to do this harm other values, such as our regard for clean water. The organization doesn’t care much about this because we’ve only paid it to follow one of our values while letting it go to work on bits of the world where we have other values. Organizations claim to have values, but who can tell if they follow them?

To control organizations we restrict them with laws. It’s hard enough to figure out whether a given company did or didn’t give proper toilet breaks to its employees. It’s virtually impossible to work out whether their decisions on toilet breaks are as close to optimal according some popularly agreed set of values.

It may seem this is because values are just harder to influence, but this is not obvious. Entities follow rules because of the incentives in place rather than because they are naturally inclined to respect simple constraints. We could similarly incentivise organizations to be utilitarian if we wanted. We just couldn’t assess whether they were doing it. Here we find rules more useful and values less for these greater than human intelligences than we do for humans.

We judge and trust friends and associates according to what we perceive to be their values. We drop a romantic partner because they don’t seem to love us enough even if they have fulfilled their romantic duties. But most of us will not be put off using a product because we think the company doesn’t have the right attitude, though we support harsh legal punishments for breaking rules. Entities just a bit superhuman are too hard to control with values.

You might point out here that values are not usually programmed specifically in organizations, whereas in AI they are. However this is not a huge difference from the perspective of everyone who didn’t program the AI. To the programmer, giving an AI all of human values may be the best method of avoiding assault on them. So if the first AI is tremendously powerful, so nobody but the programmer gets a look in, values may matter most. If the rest of humanity still has a say, as I think they will, rules will be more important.